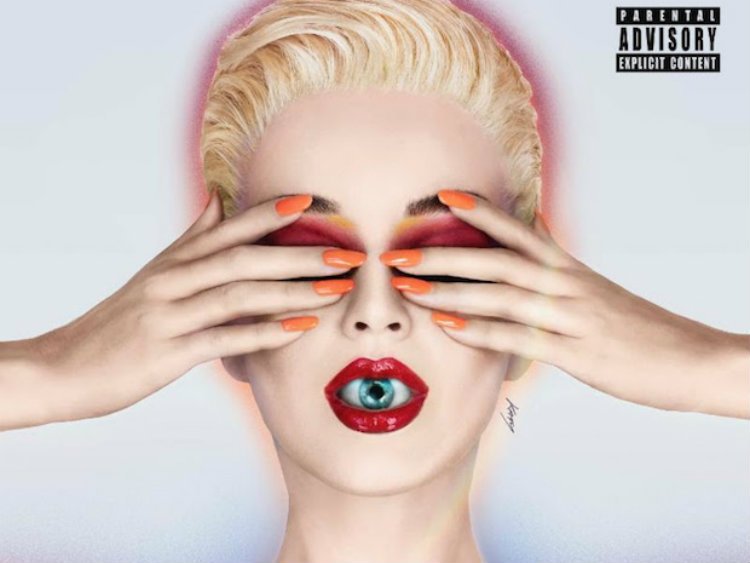

An autopsy of Katy Perry’s ‘Witness’

It’s been a while… *cue the angelic harmony’s on Britney Spears’ most underrated single, “Break the Ice”*

I have gotten better about uploading to this blog regularly, but it’s now been over a year since I last tackled a failed pop album in my Flop Masterpiece series. Maybe I put off starting this overwhelming post because I always knew what my next entry would be: Katy Perry’s 2017 Witness, an album that lives in infamy not only for its individual underperformance, but for being the first major “flop” of a megastar’s now flailing music career.

With her last two albums’ (Witness as well as 2020’s Smile) underperformance, it’d be easy to forget how dominantly Katy Perry reigned over pop music of the early-to-mid 2010s. Her debut single, “I Kissed a Girl,” in 2008 hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 just weeks after its release. The track and its corresponding album, One of the Boys, cemented the persona of Katy Perry as they introduced her, with visual references portraying Katy as a pin-up girl of the late 2000s–a modernized, live-action Betty Boop who’s provocative only as much as she embodies an ironic caricature of female pop-stardom.

Katy’s debut follow-up album, 2010’s Teenage Dream, broke records when five of its singles reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100, an accomplishment only shared by Michael Jackson’s iconic album, Bad. The Teenage Dream roll-out fittingly centered around a concept both pop critics and fans often deem the genre’s nutritional equivalent: candy. With a Candy Land themed music video, cotton-candy clouds on the album’s cover, and scratch-and-sniff cotton-candy stickers on limited-release records, Katy secured her status as the most bubblegum of popstars. Her clothes, hair, music videos, stage shows, etc. all aimed to be cartoonish and playful, taking the pop theatrics of acts like Lady Gaga and Madonna but replacing their iconoclastic provocations with a reverence for childlike nostalgia.

By 2015, Katy broke records again when she performed at the Superbowl XLIX halftime show, earning critical acclaim for her set while pulling in over 4-million more viewers than the game itself and becoming the most-watched halftime show in the network’s history. Prism, the album which preceded the Superbowl, had a weaker commercial performance than Teenage Dream despite its first week sales being her greatest to date. Two of Prism’s singles reached number one on the US Hot 100, a slight disappointment from Teenage Dream’s record-breaking triumph, but the album marked the last time a Katy Perry track would reach chart-topping status when “Dark Horse” hit number one in early 2014.

Witness was the first in Katy’s discography to be considered a true flop. Like her two albums preceding, it debuted at number one on Billboard charts, but today, Prism has sold more than four times as many copies worldwide. Since Katy is known as a “singles artist” rather than an “album artist,” the failure of Witness to spawn any chart-topping tracks revealed her true fall from glory. “Chained to the Rhythm,” the album’s lead, debuted and peaked at number four on the US Hot 100. The following four singles failed to crack the top 40, two of them not making it onto the Hot 100 at all.

Some trace Katy’s pop slump back to “Rise,” an anthemic electronic pop song she debuted for the 2016 Summer Olympics, a year prior to Witness, which peaked at number eleven on the US Hot 100. With songs like “Roar,” “Firework,” “Part of Me,” and now “Rise,” self-empowerment bops were becoming Katy’s schtick, but the world in 2016 wasn’t quite what it had been in the years she was ruling the charts. Political unrest was spreading throughout the country, largely sparked by the 2016 election which would title Donald Trump the president-elect as well as ongoing protests for the Black Lives Matter movement and the Internet uprising of the white-supremacist alt-right.

The rise of streaming platforms was also prompting audiences to explore deeper niches of music that wouldn’t have survived in a radio-driven market. 2016’s biggest music moments centered around albums rather than singles and those albums (Kanye West’s Life of Pablo, Frank Ocean’s Blonde, David Bowie’s Blackstar, etc.) were presenting their respective artists more often than not at their most experimental–a word which has rarely applied to the work of Katy Perry whose brand of candy-clad power-pop didn’t fit into the same world where Beyoncé was surprise-dropping visual albums interweaving themes of racial injustice into narratives of personal betrayal after referencing the Black Panther movement during her own Superbowl performance.

Katy’s first track of 2017 seemed aware of this cultural shift as Witness’s lead single, “Chained to the Rhythm,” attempted to acknowledge its artist’s supposed political awakening. Following the loss of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, Katy was moving to rectify her apolitical impact, motivating her to promote her then-upcoming album with a phrase that would haunt the era then-on: “purposeful pop.”

Lyrically, “Chained to the Rhythm” criticizes complacency and implies a need for activism, referencing the “rose-colored-glasses” of escapist pop media, but what that activism should confront is unclear. The music video takes jabs at conformity, mocking a sort of Stepford-wife, 1950’s Americana, and there’s a scene that depicts “the universe’s greatest ride” as a giant hamster wheel to suggest a worldwide rejection of progress. More specific political undertones can be inferred–houses are lifted up and fall back down in another amusement park ride, possibly a reference to housing market bubbles and their crashes, and citizens are shown drinking flammable H₂O, possibly a reference to the world’s ongoing water crisis–but these topics aren’t deeply explored. Katy proposes no call to action or blame-laying, making it hard to say what she thinks the solution to the world’s issues should be other than the public should be aware that they exist; you’ll still have to do the research to figure out what the issues are for yourself.

None of this is necessarily a criticism of Katy. A song doesn’t need to read as a carefully thought-out dissertation to be culturally substantive, but with the branding of “purposeful pop” as a politically-charged endeavor, Katy’s politics weren’t quite hashed out enough to go beyond the artistic activism of her peers. Beyoncé’s Lemonade of the year prior was a decisively defiant album exploring the political and social disempowerment of black women in America, and even on the dance-pop end, Lady Gaga had already attempted to enter political conversations six years earlier, writing about LGBTQ liberation and her pro-immigration beliefs back on 2011’s Born This Way. During Witness promo, Katy changed her Twitter bio to deem herself an “activist,” but more so than some of pop’s biggest names, it was exceptionally hard to decipher what causes Katy was advocating for other than the vague idea that activism is a good thing.

Still, as an intro track to Katy’s purposeful pop, “Chained to the Rhythm” was fine. Audiences could assume her foray into acknowledging the world had problems was merely an opener for a deep dive into her personal politics or the current state of the world. Maybe, some hoped, a Katy Perry political revolution would truly be ignited on the singles to come. Then, she released “Bon Appetite,” a trap-inspired pop song about eating a woman’s… buffet spread.

An argument could be made for the feminist themes of “sexual liberation,” but the innuendo references to oral sex were nothing new for Katy Perry, making the song a hard sell for this new brand of political/purposeful pop. Her choice of collaborators compromised that idea as well; in 2017, Migos, the group featured on “Bon Appetit,” was already on trial in the court of public opinion for various credible accusations of homophobia. Perhaps some of Katy’s political opinions were hard to parse, but she was always a supporter of LGBTQ rights and had that year received an award from the Human Rights Campaign for LGBTQ advocacy. Working with noted homophobes in the midst of her woke-popstar era was a bad look, exacerbated by a panned Saturday Night Live performance that ignited rumors claiming the originally-planned performance of “Bon Appetit” was botched after Migos refused to go on stage with drag queens. Katy, according to the claims, cut the drag performers before the show to keep Migos on board, thereby painting her as a faux-ally.

The rumors weren’t true, evidenced not only by dancers involved who denied the claims but also the fact that there are visible drag queens in the aired set. Comments under the performance’s YouTube video to this day still exhibit how far the fabrication has spread; the lie about Migos and the drag queens are now a part of the Witness narrative, with many adding to the mythology that Migos’ unprofessionalism caused Katy to have a panic attack before taking the stage.

I can’t find any evidence of this supposed panic attack and the only reasoning I can think of for the rumor is a fan-led defense of Katy’s disappointing performance. Marketing her purposeful pop through appeals to community, Katy and her team crammed whole casts of diverse dancers onto SNL’s set which, even if well-intentioned, made the performances’ staging look awkward, uncoordinated, and reeking of tokenism. Katy’s stage presence as well, while normally that of an A-class popstar, was total cringe–doing the dab and reveling in the subdued coolness of her hip-hop companions on “Bon Appetit,” and letting herself get sidelined by a living meme, “backpack kid,” on the live debut of Witness’s third single, “Swish Swish.”

Memes were becoming an unfortunate crutch for Katy. During her 2015 Superbowl performance, viewers took notice of two dancers costumed as sharks in the background of her beach-themed set. When one shark appeared out of step from the other’s more precise choreography, “Left Shark” became an ironic icon of the Internet for weeks after the show. Katy and her team were unwilling to let the meme fade peacefully and Left Shark made multiple appearances during Witness’s promo campaign–waking Katy up during a four-day-long live stream and receiving his own segment during the Witness tour more than two years after the meme’s peak popularity.

At least Left Shark was Katy’s gag to beat to death. Her over-reliance on other Internet inside jokes during the promotion of “Swish Swish” evokes a second-hand embarrassment that is almost unbearable, first with backpack kid on SNL (which I, for the record, think was more cute than cringe), then with a repeat appearance from the kid on the official music video along with Doug the Pug, Christine Sydelko (of Vine fame), “Crying Jordan” (this time, Crying Katy), and more.

Reviews for the video were abysmal upon release. Dave Holmes wrote an article for Esquire viciously titled, “Katy Perry is Doing a Great Job… at becoming history’s most aggressively unfunny pop star,” wherein he states, “‘Swish Swish’ leaves you exhausted, annoyed, confused, and a good seven years older than you were six minutes ago.” Constance Grady of Vox called the video “weak,” while Jordan Sargent of Spin deemed it just plain “bad.” Looking at Katy’s career in the context of her promo’s success could lead onlookers to consider “Swish Swish” an overall failure and though it did flop on the charts compared to her past hits, the track itself wasn’t nearly as lamentable as its bombastic packaging.

Essentially a diss track against “Bad Blood” (the track which ignited this musical feud) singer Taylor Swift, the song is a collection of wit-attempting comebacks; some of them are successfully cheeky (Katy rhymes “another one on the basket” with “another one in the casket” which is fun, and Nicki Minaj contributes a great verse as well) but others come across as toothless and uninspired (she says Taylor is “as cute as an old coupon, expired”). Considering “Bad Blood” is Taylor’s least lyrically-sophisticated track, I’d call the dispute a draw, but “Swish Swish” might still be the superior song in musical composition. Taking inspiration from 1990’s house music, the “Swish Swish” backing beat makes for a bold, almost retro club banger, and Katy’s sparse vocal contributions on the chorus leave space for the instrumentals to indulgently command the track.

It’s a shame the failure of the music video along with the feud-driven lyrical content overshadowed much of the “Swish Swish” conversation since Katy’s house influence was later mirrored on more acclaimed work of recent years. When Lady Gaga released “Sour Candy” in 2020, some fans noticed similarities between the two songs, namely because both sample Maya Jane Cole’s 2010 track, “What They Say.” Gaga’s 2020 album, Chromatica, was then praised for her ‘90’s house references, but with “Swish Swish” and other tracks from Witness exploring those sounds three years earlier, Katy maybe missed some credit for being ahead of that curve.

If ever a #JusticeForWitness movement emerges, it might find success in celebrating the album’s sonic explorations; Katy’s more overblown anthemic pop of the early-to-mid 2010s sounds instrumentally flat compared to most of Witness’s more carefully layered textures. At the moment, the album has a Metacritic score of 53, indicating mixed critic reviews, but even her most successful albums achieved about the same–Teenage Dream actually comes in lower at 52 and the breakthrough debut One of the Boys scored Katy’s career lowest at 47. While the era’s gained a regrettable reputation among pop stans, if you like the work of Katy Perry, Witness is a fine continuation of her discography.

The album only suffers from one main problem that then bleeds into two categories: it’s half-hearted. With an electro-pop through-line, Witness is Katy’s most cohesive album sonically, but as one of the 2010’s best singles artists, that’s not saying much–jumping from dancehall to trap to ‘90s house to dream-pop to power-ballad just on the album’s five singles alone. Succumbing to old habits again, Ms. “Do-you-ever-feel-like-a-plastic-bag” remains in her comfort zone of figurative language throughout the record despite the album’s politically-leaning promo implying a need for concrete exposition that’s rarely realized.

That promo did more damage, though, than just setting up for lackluster lyrical content.

With the branding of purposeful pop and her attempts throughout the era at political wokeness, the problematic aspects of Katy’s career came to the surface during the Witness campaign. Much of the criticism was fair; in June of 2017, she sat down with prominent Black Lives Matter activist DeRay McKesson for McKesson’s podcast, Pod Save the People, and discussed some missteps of her early career, specifically instances of cultural appropriation which are numerous in the Katy Perry iconography. Most of Katy’s talking points feel empty. She rebukes her past appropriations but never takes full accountability for or displays a complete understanding of their harm, explaining to McKesson that she’d discovered her donning of braids in the 2014 “This Is How We Do” music video was wrong because she didn’t understand the “power” of a black woman’s hair, but neglecting to acknowledge the white supremacist ideologies that necessitate such empowerment through cultural expression (she also fails to admit she looked fucking awful in that hairstyle).

Despite some praising Katy for her apparent willingness to change, others considered her efforts a weak attempt at correcting her image to sell records. The interview sparked such backlash that McKesson eventually felt compelled to address the controversy through a 19-part thread on Twitter.

Ignorance is not an excuse, especially when you’re a multi-millionaire popstar who could have done some research before opening the American Music Awards in a geisha-inspired kimono, but Katy at least deserves some credit for how far her social politics have come.

Upon entering the pop scene, Katy ignited mild controversy with “I Kissed a Girl,” a song of sapphic exploration deemed invalidating by actual lesbians. Even if the song is now a 2000s pop classic, many of the lines are straight-up offensive, like the portrayal of Katy’s female lip-mate as an “experimental game” whose name doesn’t matter, or the claim that kissing other women is “not what good girls do, not how they should behave.” But Katy’s upbringing makes these harmful expressions unsurprising. She sings on the song that her “head gets so confused” trying to reconcile how kissing other women “feels so wrong” yet “feels so right,” possibly expressing an inner conflict that wasn’t just bisexual-bait marketing but a genuine crisis of identity. In her 2017 HRC acceptance speech, Katy admits both that she’s done “more” than just kiss another woman (a statement that, among other things, fuels my curiosities surrounding her former “friendship” with Rihanna) and that as a young girl she attended pro-conversion therapy youth groups and “prayed the gay away.”

The piousness of Katy’s family has never been something she’s hidden (before taking on the persona of Katy Perry, Katy began her career as a Christian rock singer under the name Katy Hudson), but the toll her fundamentalist upbringing had on her emotional development became more obvious with Witness than any album cycle prior.

On the day of Witness’s release, Katy began filming Witness World Wide, a 72-hour YouTube livestream that was something between a four-day variety show (featuring an array of guests from Neil DeGrasse Tyson to Caitlyn Jenner to Dita Von Teese) and a Big Brother-style candid documentary. (If I have any criticism of the program, it’s that it should have leaned further into the latter category.) The show’s most memorable hour revolves around a filmed therapy session with Dr. Siri Sat Nam Singh from Viceland’s series, The Therapist. Early on, Katy compartmentalizes her internal experiences as her celebrity persona, Katy Perry, and as Katheryn Hudson–her private, childlike self represented by her own birth name.

She describes the emotional development of Katheryn as not “evolved,” explaining that her Christian upbringing left her feeling trapped within a spiritual “bubble,” saying:

“I was a very curious person, and the curiosity… sometimes it wasn’t allowed because you had to have faith. So it was hard for me sometimes to be curious about what was going on in the rest of the world… It was like just ‘Do as I say, no “if,” “ands” or “buts”’… It’s not that I wasn’t allowed, it’s just that, like, it wasn’t normal for people to ask questions in my position.”

As a child, Katy and her siblings weren’t allowed to intake much pop culture in fear of its secular influence or eat Lucky Charms cereal since, according to her mom, “luck is of Lucifer.” Katy often speaks of the love she has for her parents, telling the New York Times in 2017 that they attend group therapy together and controversially supporting her father’s “nonpartisan” apparel line in 2020, but their relationship is at times contentious. Her parents reportedly have called Katy a “devil child” during sermons at church services where they asked church-goers to pray for their bicurious songstress daughter.

“Chained to the Rhythm” might have been her most outward-reaching song, but the album track “Power” embodies the true enlightenment of Katy Perry. Donald Trump, a blatant racist and misogynist, represented an oppressive male figure Katy found familiar–a representation of her fundamentalist father. She described the distressing event of Trump’s win to the NYT, saying, “I was retriggered by a big male that didn’t see women as equal. And that had been, unfortunately, a common theme in my upbringing.” On “Power,” she sings in the first verse, “I am my mother’s daughter/And there are so many things I love about her/But I have to break the cycle/So I can sit first at the dinner table.” It’s primarily a breakup song just as Witness is primarily a breakup album, but it has a spark of political angst. The patriarchal dynamic that bounds Katy’s mother to never sit first at the table is reflected in the misogynistic culture that elected Trump president.

As an album and an era, Witness works best as “purposeful” when exploring the process of unlearning behaviors. It can dip into political and social conversations, like on “Power” or “Chained to the Rhythm,” but it’s on the more personal tracks too; “Deja Vu” explores the cyclical nature of Katy’s relationships, past and present romantic disenchantment “running on a loop,” while “Mind Maze” seems to echo the same discontent applied to Katy’s career and public persona, wondering if she needs to “start over, re-discover.”

During the livestream, Katy and Dr. Siri emphasize that healing is a process not an overnight epiphany, but Witness stumbles when Katy seems to think she’s further down the journey of self-discovery than she actually is. At times, the Witness album cycle seems less like a promotional campaign for the record and more of an apology tour for Katy’s problematic past–copping up to her cultural appropriation with McKesson, saying she’d re-write lyrics on “I Kissed a Girl,” then doing a mid-era 180 on her feud with Taylor Swift, changing lyrics in “Swish Swish” from “Don’t you come for me” to “God bless you on your journey, baby girl” during live performances. Maybe Katy moved past her anger in those months or maybe she realized forgiveness would be the more enlightened thing to present. Either way, it proved that at the start of the era, Katy didn’t have a firm grasp on what her and her music were trying to say, extending to her attempted political awareness. She adopts buzzwords–“safe space,” “empowerment,” “liberation,” “conscious”–but employs them with the non-specificity of a marketer rather than an impassioned activist, not because her crusade is inauthentic (I don’t think) but because she’s so eager to be involved in the discourse that she skips past forming a real political stance. All she knows is popping the bubble.

Music and performing became an outlet for Katy to escape the bubble of a repressive childhood, but the confines of being Katy Perry, the popstar, is sometimes as spiritually limiting. Midway through the livestreamed therapy session, she admits to bouts of alcohol dependency, expressed on the Witness track “Dance With The Devil,” and claims that drinking helped quell the pressure of her celebrity status. Immediately following the first fall of tears in the session, Katy talks about a subject that’s become intrinsically linked with the narrative of her downfall: the blonde pixie-cut she debuted in 2017.

This will be the fifth entry into the Flop Masterpiece series and the third to incorporate some sort of popular “breakdown” narrative for its discussed artist. Katy’s public behavior was not quite as odd as Lady Gaga’s disconnected interviews and committed performance art during the ARTPOP era, but sobbing during a recorded therapy session within your 72-hour livestream does raise concerns about a possible mental health crisis. Even if Katy’s vulnerability was praise-worthy, displaying your trauma to an audience of strangers could potentially cause more discomfort than healing.

Unlike Britney Spears in 2007, Katy at least seemed in the driver’s seat for her career’s unraveling–avoiding the extreme exploitation of 2000’s celebrity culture–but the stories of both women’s popular declines have revolved around physical appearance to an uncomfortable degree. It’s no coincidence that Britney and Katy were at their most publicly chastised in the years they cut their hair. Circumstances for the changes were different–Britney shaved her head in view of paparazzi during what she called a moment of “rebellion,” while Katy chopped off most of her hair following constant bleaching which left it damaged and falling out–but the effect was the same; neither star wanted to represent the image of a pristine pop princess in sacrifice of their humanity. Katy could have found a realistic-looking wig or attempted some form of hair-extensions to retain the image of her famous long-locks, but she didn’t. “I so badly want to be Katheryn Hudson,” she said to Dr. Siri. “That I don’t even want to look like Katy Perry anymore sometimes.”

Adherence to hyper-feminine beauty norms established Katy as a sex-symbol from the start of her career. Once she choose to reject the standards her persona previously embodied, she was deemed unsexy, unappealing, and unstable. Katy knew it within the Witness era, telling Dr. Siri that the backlash to her short hair hurt her and made her feel like she can’t be her “authentic self” in the public eye.

In some ways, the adverse reaction was understandable. Rightly or wrongly, we as a society associate certain types of people with certain physical attributes–consider the stereotype of the “dumb blonde” or the even stranger notion that intelligent people wear glasses. Katy Perry’s playfulness was considered sexy and fun when she employed the aesthetics associated with youthful femininity, including her long dark hair. When she started rocking a pixie-cut, a hairstyle associated in our culture with women who are either old or traumatized, the exuberance Katy once profited from suddenly seemed desperate and out-of-touch. Hosting the VMAs in 2017 (an event most people seem to have forgotten about), her jokes about fidget spinners and ripped jeans paint the short-haired Katy less like a global popstar and more like a middle-aged woman who needs her teenage nieces to think she’s cool (I wish I didn’t feel this way, but the whole thing gives such drunk-Aunt vibes and that’s not my fault).

Still, the negative response toward Katy’s hair, even from her own fans, became suffocatingly dramatic. Like the backlash to Britney’s 2007 baldness, how this change in aesthetic affected Katy’s public standing revealed the misogyny that still pollutes modern pop standoms. Fans mourned Katy’s hair as if its shorter length indicated her retirement–like she wasn’t capable of writing bops or putting on a spectacular stage show all because she didn’t look like a bombshell pin-up anymore. Even recently, when Katy dyed her now grown-out hair back to black, stan Twitter erupted in celebration of her physical return to form.

There’s nothing wrong with fans’ elation (when I see a new photo of Lady Gaga in a pair of 9-inch platform heels, I’m similarly overwhelmed with hopes for a new pop era) but even this positive attention implies something about how audiences cling to an artist’s image at the occasional constraint of said artist’s personhood.

Katy Perry said during the Witness cycle that she wanted to return to Katheryn Hudson; she was abandoned by the public in the process.

In many ways, Witness is one of Katy’s strongest records to date, especially in its relative sonic cohesiveness and voyages into 1990’s house music. Katy herself doomed the era by overemphasizing its barely-there political undertones leading to a public response hellbent on proving she was never that progressive, but it’s hard to imagine her succeeding with another era of escapist anthemic pop following America’s burgeoning political turmoil (it certainly didn’t work for her 2020 album, Smile).

We wanted Katy to evolve just like Katy wanted Katheryn to evolve, but in some ways, Katy’s method of healing went outside our society’s comfort zone for progress. Perhaps her artistic growth was stifled by a stan culture that wanted her to advance musically and politically without sacrificing the hyper-feminine beauty norms that made her a star. The images of pixie-cut Katy have become synonymous with her perceived failures as a popstar, but it’s no wonder Katy’s found herself stuck in these bubbles–the bubble of her family’s conservatism followed by the bubble of her celebrity persona–when her audience expected her image to adapt with cultural shifts whilst simultaneously limiting her aesthetic expression.

Maybe when stan culture accepts that Katy Perry’s long black hair is not the nexus of her talent as a popstar, we can finally acknowledge that Witness was always a fine pop album. And “Roulette” is one of the best tracks of Katy’s entire career.