‘Blackout’ by Britney Spears: an album ahead of its time by being perfectly of its time

This blog is tragically neglected, however despite some large personal setbacks caused by the ongoing hell that is this global pandemic and overall year, I have managed to get *some* posts uploaded. The number is still in the single-digits, but I think I’ve made at least two things clear: 1) I have huge respect for pop music, especially pop music that’s somewhat unappreciated or infamous, displayed by my series, “Flop Masterpiece,” where I look at pop albums that “flopped” and the cult followings behind them, and 2) I know way too much about Britney Spears. Today, we’re going to combine my two passions and dive into Britney’s 2007 magnum opus: the inevitable and infamous flop, Blackout.

It’s a little weird to put Blackout in the same category as the other “flops” in this series so far. Albums like ARTPOP, Electra Heart, and Bionic certainly have developed their own devoted audiences, but they’re still largely considered to only have cult followings. Even with some positive reevaluation in recent years, none of these three have broken through as mainstream successes the way that Blackout has.

At the time of its release, though, Blackout was the biggest flop of Britney Spears’ career. Numbers-wise, it produced her lowest album sales yet–selling roughly half the copies as her previous full-length release, In the Zone, in its first week. Blackout also became the first in Britney’s discography to not debut at number one on Billboard charts (stans will be quick to point out this is only because of a last-minute rule change, however the change was completely fair and The Eagles of all people outsold Britney by over double despite releasing via one retailer). Sales were certainly not pitiful, but the standards for Britney’s success were already set impossibly high with her debut nine years earlier. Today, Blackout’s worldwide sales have reached barely over 1/10th the number of copies sold by her breakout ...Baby One More Time album, released when Britney was just 17 years old.

How the album did critically is a little hard to gauge. Metacritic puts the album at a score of 61 based on 24 reviews, indicating a “mixed” response, but reactions from top publications–some of which were not present in Metacritic’s critical pool–(like NPR, The Guardian, Pitchfork, etc.) lean far more positive than this score would suggest. None of the original reviews, however, deal with the album’s content exclusively. For critics at the time–and even critics now–it was practically impossible to separate Blackout, the album, from the surrounding context of Britney Spears’ chaotic life. Nearly every review seems as equally preoccupied with her personal struggles as they are with the music: NME’s opens with the question, “What’s pop’s most plastic princess to do when her life has turned into absolute gold for the tabloid masses?”, the New York Times’ begins with quotes from Britney outside a court hearing a few days prior to Blackout’s release–the iconic lines, “eat it, lick it, snort it, fuck it” (NYT left out the “fuck it” part)–and the second sentence of Rolling Stone’s mentions Britney’s constantly-fluctuating custodial time, joking that some of the album’s lyrics “may be enough to make Sean Preston [Britney’s son] use Jayden [Britney’s other son] as a protective shield from mommy.”

Critics would become far more supportive of the album’s content in years following, but in 2007, any discussion of Britney Spears was dominated by contempt for her imploding public image.

The fixation was almost understandable. Prompted by a nasty divorce, estrangement from members of her family as well as the death of a beloved aunt, and abuse by her own “manager,” Britney’s home life was collapsing around her, creating a public downfall that was somewhat unprecedented. Once Britney began acting out, the entertainment that came from her bizarre behavior worsened issues as paparazzi ceaselessly hounded her to cash in on any stories that would inevitably come from her emotional disintegration. By January 2008, the Associated Press was sending an internal memo to staff reading, “Now and for the foreseeable future, virtually everything involving Britney is a big deal,” while publicly admitting to having Britney’s obituary prepared and claiming her death would “easily be one of the biggest stories in a long time.”

Even the most ignorant of celebrity gossip would find immense trouble ignoring the dramatic saga of Britney’s popular decline while coverage on it was morphing into a ‘round-the-clock business. But not every review that backgrounded Britney’s work with discussions of her personal struggles did so just to please drama-obsessed readers. Part of Blackout’s appeal is in how the album embraced the chaos of Britney’s life, making the context of her public image not totally irrelevant to the story her music was trying to tell.

“Gimme More,” the album’s lead single, is a near-perfect representation of the complicated legacy Blackout has left behind. It’s a pop track so undeniably strong that critics immediately commended it as a highlight of the record and one of Britney’s strongest singles. The opening line–“It’s Britney, bitch”–has become the most quotable phrase of her entire career (even better than “eat it, lick it, snort it, fuck it,” if you can believe it), and fans, both of Britney’s and of pop music as a whole, have continued to hail the track as one of the greatest “ho anthems” of all time.

Unfortunately, “Gimme More” is still at the center of one of Britney’s most infamous public blunders when, during a performance of the song at the 2007 MTV VMAs, an obviously out-of-it Britney took the stage for possibly her worst public appearance to date–full of half-hearted lip-syncing, noticeable stumbling, and facial expressions that indicate disinterest at best and total dissociation at worst.

The VMAs had been preceded by months of negative press following the breakdown of Britney’s personal life as well as her emotional well-being. She was out all night most nights, spoke in bad British accents, went in and out of rehab, and, most infamously, shaved her head in view of paparazzi as a symbol of “rebellion.” The public was convinced Britney Spears had lost her mind and the disaster of her attempted MTV “comeback” only proved to many that Britney wasn’t someone worth taking seriously. She was a trainwreck sort of entertainment–deserving of contempt or maybe pity, but never any real sympathy or respect.

During such a chaotic period of her life, it’s a miracle that Britney and her team managed to record and release an album at all, and especially a miracle that the recording process has never become a source for tabloid gossip. Everything surrounding the album–including its own promo–has a messier history. Most professional obligations during Blackout’s promotion didn’t seem to concern Britney. As far as we know, there were only two scheduled interviews during which she planned to discuss the album at all: one she never showed up for and one she called into a radio hour for, then abruptly walked away to take a shower. Britney didn’t seem interested in being a popstar anymore but that didn’t mean she wasn’t still interested in pop music. On the contrary, it’s during this tumultuous period that Britney seemed to take more control of her work than ever before.

In recent years, much lore has spread within stan communities about a “lost” Britney album from 2004/2005: The Original Doll, a supposed “experimental” collection which Jive Records allegedly refused to schedule internally due to its deviation from Britney’s already cultivated pop-persona. “I think maybe [Jive] thought it was not close enough to her brand,” claimed songwriter Michelle Bell to Buzzfeed in 2014. “I think the record label was like, no, you've got to stay the course you're on, which was a strong pop star, a little longer.” If ever there were a real Ashley O of the American music industry, Britney Spears–even Britney Spears pre-conservatorship–would be her; but if her lack of control came from her record label’s concerns over her image, Britney would only gain authority over her music once she had already tarnished that image herself.

Though she only has writing credits on two of Blackout’s tracks, it’s the one album in Britney’s discography in which she’s credited as the executive producer. Who’s to say exactly what that means on this project–the term itself is pretty vague–but it’s hard to find an album within Britney’s career that sounds more relevant to her life in the time it premiered. It may have been Britney’s particular flair that gave albums like ...Baby One More Time and Oops!...I Did It Again the push they needed to succeed, but much of those songs could have been recorded by practically anyone working in mainstream pop at the time. Blackout, on the other hand, could have only been released by Britney Spears, and only by Britney Spears in 2007.

For the first time in her career, Britney had reached a point of continuity between her work and her life. Songs like “Slave 4 U” in eras prior utilized innuendo and exploited a modest kind of sex appeal while Britney’s team continued to market her as a good, abstinent, Southern Baptist sweetheart. By 2007, her celibacy was long gone, but instead of cowering from the slut-shaming lobbied against her, Britney was embracing it–personally and professionally. She was being photographed in strip clubs and she was making music for them too.

Besides the “bitch” of the opening line, none of “Gimme More”s lyrics are explicit, but they’re backgrounded by moans and breathy vocals that can only evoke one type of activity–the type early-era Britney would have claimed to be a stranger to. On Blackout’s deeper tracks, the fun gets trashier in the best possible ways. The verse of “Perfect Lover” contains the very straightforward line, “Don’t you wanna see my body naked?” neglecting any sort of demure sensuality for an unabashedly sexual expression. “Ooh ooh Baby” is allegedly inspired, in small part, by Britney’s relationship to her newborn sons, but one of the opening lines is “You know I have an appetite for sexy things,” followed by a repeated, “You’re fillin’ me up, you’re fillin’ me up,” during the chorus that I can’t help but read as anything child-appropriate. Then there’s the bluntly titled bop, “Get Naked (I Got a Plan),” a Danja produced track alongside “Gimme More” that feels like a direct, even sexier sequel to the single, featuring many of the same hypnotic attributes as “Gimme More” then experimenting on top of them with warped autotune, making the whole track feel like “Gimme More” on hallucinogens.

Blackout has earned a reputation as a trendsetter, sometimes referred to as the “Bible of Pop” for its influence on music of the following years. Lady Gaga took much of the credit for the revival of EDM in pop with the release of The Fame in 2008, but Blackout already broke that ground a year prior, experimenting with auto-tune, electropop, and dubstep far before those sounds had hit mainstream radio. When Gaga debuted “Telephone” as a single in 2010–a song initially intended for Britney’s following album Circus–Rob Sheffield wrote for Rolling Stone,

“‘Telephone’ actually sounds a lot like Britney’s 2007 hit ‘Piece of Me,’ proving yet again how much impact Britney has had on the sonics of current pop. People love to make fun of Britney, and why not, but if ‘Telephone’ proves anything, it’s that Blackout may be the most influential pop album of the past five years.”

Sheffield doubled down on this sentiment again in 2016. “When [Britney] dropped Blackout in 2007,” he said reviewing Britney’s latest (and second greatest) album, Glory. “The music industry scoffed, but then proceeded to spend the next few years imitating it to death, to the point where everything on pop radio sounded like Blackout.”

At the time of its release, a handful of Britney’s contemporaries–Rihanna, Beyonce, Kelly Clarkson–publicly claimed a love for the record. In recent years, some of indie pop’s most adventurous darlings–Charli XCX, Kim Petras, Slayyyter–have continued to hail Blackout as a primary inspiration for their own work. There’s an argument to be made about Blackout being an early influence, or at the very least predictor, of the current “hyper pop” genre now speculated to be “the future of pop.” By late last year, Rolling Stone was calling the album the number one biggest influence on pop of the 2010s; but Blackout was ahead of its time for reasons far beyond just its sound.

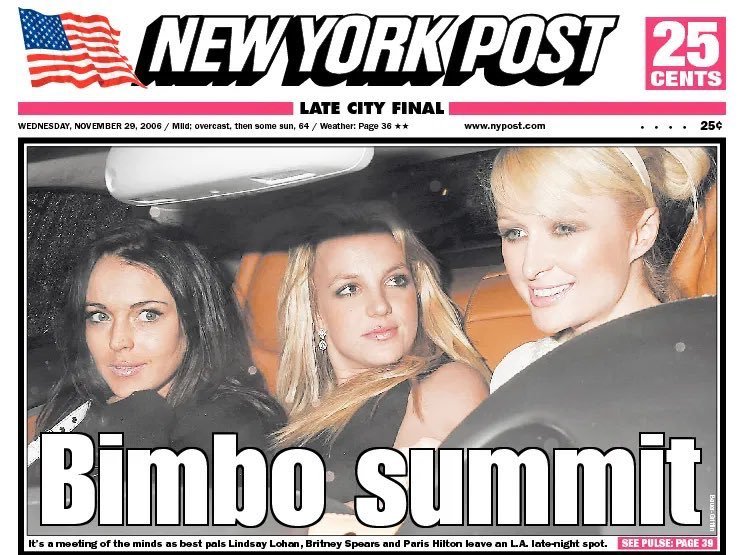

In the years 2006 and 2007, images of Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Britney Spears on all-night benders were plastered across tabloids, TVs, and blogs as a way of public humiliation. Every late-night outing the women embarked upon (whether together or not) became a news story and talking point, not because the three were doing anything particularly interesting (Paris got caught with cocaine once and Lindsay got some DUIs, none of which is uncommon in the world of celebrity) but because they could be easily cast as tabloid villains meant to represent everything we deemed wrong with our society, especially our young women. Newsweek’s first issue of 2007 emblazoned a picture of Britney and Paris on the cover with the tag “Girls Gone Wild,” claiming that “out-of-control celebs and online sleaze fuel a new debate over kids and values,” then pondering within the pages on how we could blame Paris, Lindsay, and Britney for “a devaluation of sex, love and lasting commitment.”

It was supposed to be shameworthy. Due to the reckless abandonment of their once Disney-approved images, Lindsay and Britney became examples of everything young girls should try not to be–sloppy, sexual, and unapologetic–yet, if you check in on stan Twitter today, it’s obvious that the photographs of these celebs’ then-outrageous behavior, once intended to shock the public with their shamelessness, are being recontextualized into something far more worthy of reverence. They’re “iconic” now.

This switch comes down to two things: one is that we’re living in a postmodern world and the Internet loves to take things once incredibly uncool–either from being “cringe” or just perceivably vapid–and make them “ironically” cool. The elitist hierarchies of “fine art” vs. “mindless entertainment” are made up on arbitrary grounds, so why not claim that Heidi Montag’s songs are just as worthy of respect and analysis as whatever Beatles album we’re supposed to validate as “real music”? Stans posting pictures of Lindsay, Paris, and Britney leaving a nightclub and captioning them “the holy trinity” is irony at its finest–upholding something generally perceived as trashy and declaring it to be on the same level as the three most important figures of the Christian religion. While these comments are certainly motivated by irony, that doesn’t make them insincere; rather, ironic and exaggerated acclaim for “trashy” media gives fans of that media opportunity to celebrate something they always found worthy of attention but maybe felt too ashamed to admit to liking.

There are a lot of people–folks of the LGBTQ community and girls/women in particular–that found Britney Spears’ 2007 antics not just unworthy of the ridicule they received but maybe also worthy of some celebration, being considered by plenty as symbols of Britney’s liberation. Even Britney’s most infamous act of self-sabotage–the shaving of her head in February 2007–garners mixed reactions from fans, some seeing it as a sad reminder of the pain she faced in her darkest times and some seeing it as the glorious rebellion mainstream media was committed to misunderstanding. Falling into the latter category, Coco Romack writes for a fantastic article in i-D,

“At the moment of her public decapitation, of sorts, when she stepped into a Tarzana, California hair salon and shaved her head, the image was immediately and forever burned into my memory. There were initial feelings of pity—I succumbed to the pity porn, I’ll admit it—but those soon dissipated, leaving other emotions in their absence.

I related to her.

This was, above all, an empowering moment. By stripping herself of her Barbie-blonde hair, considered desirable for the pop starlet that was sexualized from a young age, Spears removed one of her clearest outward symbols of femininity. Liberated from the money-making vehicle, she took control of her body. For the star who was rarely at the wheel of her life or career, this was perhaps one of the first times.”

Blackout has no overt political or social messages, but the way each song resists the temptation to correct Britney’s misogyny-driven public downfall results in the record achieving a rare sort of feminist-pop status that never feels pandering.

Private battles, like her break from ex-husband Kevin Federline, become subjects on “Toy Soldier” and “Why Should I Be Sad”; her known penchant for nightlife is explored on tracks like “Freakshow” and “Get Back”; and even the suffocating nature of fame laces the subtext of the first single, “Gimme More,” then takes center stage on the second, “Piece of Me.”

Blackout is an album about partying and drinking and getting lost in the chaos of excess, most songs suited for a night on the dancefloor where no fucks are given and many shots are taken. It’s also an album about divorce, notoriety, and the struggle to control your own narrative. As much fun as Blackout is, it's weighted by topics significant to Britney’s life, each new theme supported by catchy hooks and dance-inspired instrumentals to make the seriousness of the subjects palatable without sacrificing a candid portrayal of its artist’s turmoil.

Unlike the content of albums like ...Baby One More Time, the music and lyrics of Blackout were never intended to create a product for listeners to pour their own experiences and wants into. Britney Spears and her music were no longer vessels for other people’s fantasies. Instead, Britney’s experiences were framed as valuable and interesting on their own, no matter their perceived relatability. For some stans, a song like “Piece of Me” was fun just for the opportunity to watch Britney clap back at her haters, embracing the identities thrust upon her and becoming “Oh my God, that Britney’s shameless.” The commentary she provides for her public persona gives the track the same appeal as Taylor Swift’s most self-referential work (think “Look What You Made Me Do” or anything else on Reputation), but even if you don’t give a shit about that–Britney’s fame or her own meta examination of it–the track still has value as a kiss-off bop in which an ill-reputed woman takes back her power and reclaims her story.

The irony is that while Blackout has been continuously hailed in the 13 years since its release as Britney’s greatest album to date, the record known for igniting her professional “comeback” came a year later with the release of Circus in November 2008.

Like all the flops we’ve discussed thus far, the reason many turned their backs on Blackout was not that the music was bad but that Britney Spears, the artist and celebrity, couldn’t retain the status she once held in the public’s eye. The girl once known for her bright smile, polite demeanor, and modest sexuality had revealed herself to be sleazier than ever marketed, and she didn’t seem sad to have her public image deteriorate.

Even when it came to promoting her own work, Britney had no interest in the traditional pop-princess album cycle. She did barely any promo in 2007; in May, there was a small House of Blue’s tour of 6 shows, about 12-16 minutes in length, however Blackout, released in October, never received its own live show nor can you find any live performances from the era (with the exception of the disastrous VMA appearance). The album’s photoshoot also appears to be lacking in material; “Gimme More”s single art and Blackout’s album art feature the exact same shot of Britney with different, equally cluttered backgrounds, and there isn’t much variance of aesthetics with other singles as well–she’s literally wearing the same outfit and hat in all of them. The album’s booklet seems so strapped for visuals, it just uses screenshots from the “Gimme More” video on the first page.

Of course, four tracks off the album did receive music videos, however, “Piece of Me” is the only one made under seemingly ordinary circumstances. “Gimme More” is still one of Britney’s lowest-effort videos, merely featuring footage of her dancing on–or even just beside–a stripper pole with no real choreography and some of the strangest editing choices I’ve ever seen in a professional popstar’s video. Rumors of a very different intended treatment have circulated Britney stan communities ever since and Britney’s personal makeup artist on set has since claimed that Britney herself “sabotaged” the shoot and director by refusing to perform the original script. “Break The Ice,” a single released shortly after Britney was placed into two involuntary psychiatric holds, seemed to have no involvement from Britney in the creation of its video and starred an animated Britney exclusively. Sometimes I wonder if she’s ever seen it.

The music video for “Radar” was not released until July of 2009, the single being placed onto Circus’s tracklist in addition to Blackout’s once the Blackout album cycle came to an abrupt halt. It’s obvious that Circus was an album created as a strategy to rectify Britney’s public image. The album covers alone speak volumes about what each record was trying to communicate: Blackout’s is full of visual over-stimulus, both dark and loud at once and showing Britney for the first and only time on an album cover with dark hair and a cool resting bitch face, while Circus’ shows a return to her signature blonde, Britney donning a white dress and looking up at the viewer from her knees with a modest smile, harkening back to …Baby One More Time’s girlish appeal.

Public perception of Britney’s “comeback” is frustrating in this sense. “[O]ur eagerness for a Spears ‘comeback,’” writes Jude Doyle for Quartz. “Seems to stem from an urge to see her, literally, return to her original teenage persona.”

Britney had spent the entirety of 2007 being shamed, ridiculed, and humiliated, yet in the middle of all that, she produced her most intriguing and beloved work to date. As time goes on, she becomes increasingly recognized for that achievement.

Today, Blackout is widely considered to be not only Britney Spears’ best album, but one of the best pop albums of recent history. In 2012, it was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 2017, multiple music journalists published articles celebrating its 10th-year anniversary where the word “masterpiece” was brought up often (Rolling Stone, a “punk masterpiece”; i-D, a “revelatory feminist masterpiece”; Billboard, “a masterpiece of [Britney’s] extraordinarily resilient career”; etc.). In 2019, The Guardian ranked it as the 39th best album of the 21st century, and just this year, Rolling Stone named it the 441st best album of all time–and there have been quite a few albums in all of time.

Despite being one of the most influential popstars in history, Britney Spears is just not the type of artist that gets this sort of critical acclaim often. Maybe that’s what makes the critical re-evaluation of Blackout so thrilling for fans. It’s the album that, by most accounts, shouldn’t have been as good as it was, but somehow has become one of the most widely respected and imitated albums of the last 13 years. It is not Britney Spears’ only good album; it’s not even her only great album. It’s just the only album in her discography that receives a proper amount of praise because it is so good that Britney’s own influence and importance could no longer be ignored, even when the whole world was rooting against her.